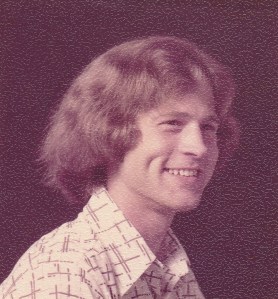

Mark Alfred Phillips was born on February 25, 1942, in St. Charles, MO, to Edith Beste Phillips and Robert Earl Phillips. Mark completed the family as the youngest of three boys. His brothers, Robert (our grandfather) and Richard, were 10 and 4 years older than Mark, respectively.

In 1944, when Mark was 2, the family moved to Quincy, IL. During the 1950s, while his brothers were away in the military and seminary, Mark lived at home with his parents, a life we imagine somewhere in between youngest child and only child, spending his time at Boy Scout Camp Saukenak and with Quincy Summer Playground Box Hockey.

In 1956, Mark went away, like most boys in his community then, to a minor seminary high school, but he did not pursue the seminary as his brother Richard (who took the name Glenn at ordination) did. There, and at Quincy College in the early 1960s, he performed in a piano recital and several one-act plays.

In 1964, Mark graduated from Quincy College and began service in the Army. While we know less about his life from here on, we are learning more over time.

We do know that on Labor Day in 1966, Mark met Cecil C. Cade at a bar in Kansas City after driving in from Fort Leavenworth. In a memorial note about Cecil, Mark wrote about holding hands while Cecil drove his convertible in those early days.

The date October 6, 1966, was important to them and appeared as a symbol with an inverted triangle in a few places in our research. We suspect that’s when they committed to being a couple.

They were together for more than 20 years, living in Chicago and Houston. While they lived in Chicago, Cecil worked as an accountant, and Mark attended Loyola for a master’s in philosophy. He also worked at a bank and at a company that managed the copyright for new post-Vatican II Catholic hymns. Mark likely demonstrated at the DNC protests in Chicago in 1968 and in Florida in 1972, the latter in support of gay rights in particular.

In 1979, they moved to Houston—we think because they wanted to be closer to Cecil’s family, including his mother, Maxine, and his great-aunt, Lomie. Mark worked at a bank there as well, and Maxine moved in with them in 1988 so they could take care of her as her Alzheimer’s advanced.

In the late 1980s, Cecil and Mark were both diagnosed with HIV. Mark participated in a study about the use of AZT in asymptomatic people. In December of 1988, Cecil started to have symptoms of pneumonia. He died in a Houston-area hospital on January 2, 1989. Mark put together an AIDS quilt square and submitted it to the AIDS Quilt Project in Cecil’s name. He also went to DC to see the quilt later that year, and their gravestone includes both of their names and that inverted triangle.

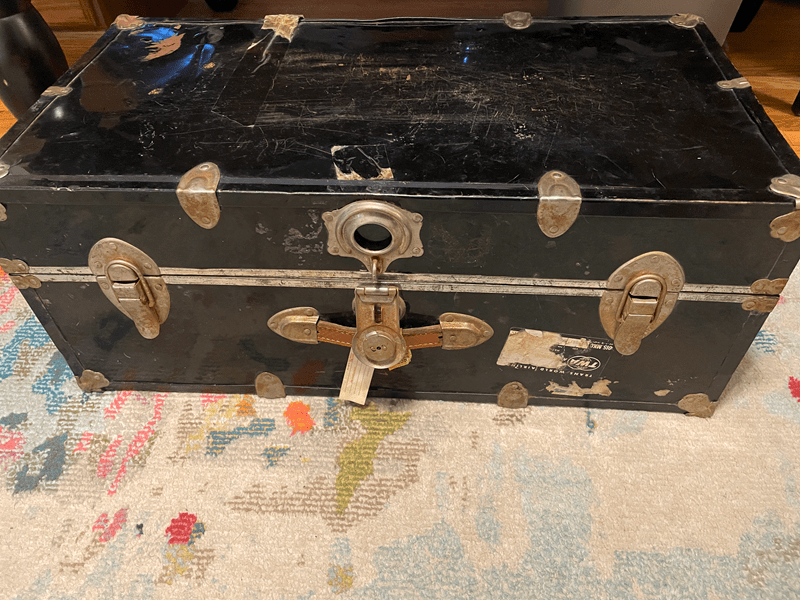

We know these scattered details about our Great-Uncle Mark due to the path that they took to us, his great-nieces. In the months after Cecil passed, Mark gathered some books, newspaper clippings, rolled-up posters, trinkets, and Cecil’s father’s Army blanket and lovingly packed them into a standard-issue army trunk (Cecil’s, we think), roughly 16 by 30 inches. He brought the trunk with him on a trip to Missouri in February 1990 and left it with his niece, Beth, our mother. The key followed months later, and both sat in storage in the attic of our childhood home, unopened, for over thirty years.

Mark passed his love of researching family ancestry and genealogical records down to Beth, leaving her a detailed binder and instructions on how to write narratives in a series of letters through the 1980s and early ’90s. She would go on to complete much of his research and conduct her own in later years. For Mark, this drive to research extended to Cecil’s family history as well. He took a course on recording oral history and went to great lengths to file a recording of an interview with Cecil’s aunt Lomie in the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Interestingly, however, he documented his own wish not to be recorded in this, our own family’s history. He also did not wish to have an AIDS quilt square.

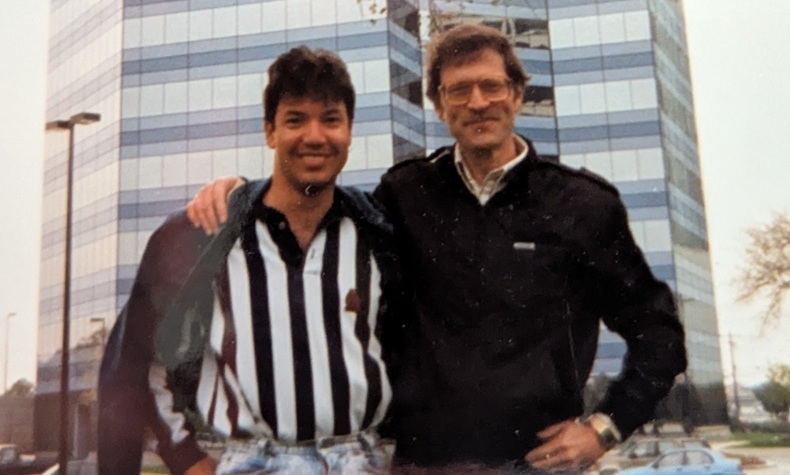

Sometime after that, Mark’s friend Rick Hernandez became more than a friend and moved in with Mark. They co-parented Rick’s son, Marcos, with his mother starting in 1996. Mark loved and encouraged Rick in his art and at work.

In the early 1990s, Mark realized that his birth family was a source of pain due to their rejection of his sexuality and the people he loved. He’d kept in touch with his brother Glenn and his niece Beth over the years, but he called Beth on Halloween night, probably in 1994, to say that she just reminded him of the rest of the family in a way that caused pain and that he didn’t want to be in touch with her anymore for that reason. We know he said something similar to Glenn around that time.

Mark died on January 1, 2009, in hospice care in Houston from pneumocystis pneumonia. Rick called Beth and Glenn to tell them what happened and to get family permission for Mark’s cremation. Mark and Rick had agreed to donate their furniture to a neighbor who had an empty apartment while Mark was nearing the end of his life, a generosity even in those tough days.

Mark had two great loves of his life, spending about 20 years with each.

About who Mark was:

Mark was known by his many beloved cousins to break into dance for no reason. Our mother fondly remembers him teaching her to waltz when she was a teenager.

He was self-aware; he knew he leaned towards bitchy or catty at times and would acknowledge that. He once wrote his earnest critiques of his great-nieces’ childhood “art” or scribbles. He was just funny.

He obtained a Masters Degree in Philosophy from Loyola University Chicago in 1970. He typed his thesis, The Common Sense Philosophy of G.E. Moore, on a typewriter. He was a lifelong philosopher, including in his letters. In one, he included a beautiful picture of a person with their hands up in a beach sunset; “Freedom is an embrace,” he said.

He wrote of his love of music, used music to remember Cecil, and had special songs with Rick; he clearly valued music as an art form and one of expression. He dabbled in poetry.

He wanted to leave something for his great-nieces and -nephews, including rare coins, currency, and artwork.

He was and is loved for exactly who he was.

He seemed to us to be a man of contradictions, painstakingly recording his and Cecil’s family histories and researching Rick’s, sending letters to our mother recording his own life history, but then saying he wished for those records not to be included in our family genealogy collection. An act of defiance to be separated with finality from a family he considered to be acting with bigotry in their hearts. It makes sense to us, but also, it’s a mystery. He will always be somewhat of a mystery to us, even as we continue to find out more than we ever thought we would know.

He at once belongs to us but not at all. He is one of us, and not.

— Anna Bilyeu and Lisa Ampleman

If you would like to add your own memories of Mark here, you can send them via the contact form on this site. We are grateful to those who have shared their stories and knowledge with us so far.

Memorial notes from others:

My cousin Mark was one of the youngest of the “old” cousins, those born in the first group of Beste grandchildren before or during the war. I was the oldest of the “young” group of baby boomer cousins born after. Most of us lived in St. Charles or nearby while the Phillips family lived in Quincy. It was always a major event when they came to visit, or we went to visit them, or—the best option—when my parents dropped me off there while they went on to a funeral or to visit more relatives in Chicago.

First of all, the Phillips’ household had fascinating tank of guppies. Second, Aunt Edith, with her teacher skills and three sons, always seemed thrilled to have a temporary daughter. Third, there was Mark with his dimples and playful personality. In the way of younger kids who look up to older ones, I adored him. OK, not so much on the day he chased me on his two-wheeler; I ran squealing up the porch steps for sanctuary and learned the alarming lesson that big kids are strong enough to push their bikes up stairs.

But that was out of character, and more usually Mark played with, and took care of, and paid me good attention, and in my unshaped and impressionistic memory of that time, he exists as a cloud of happiness, laughter, and affection. When I compare my recollection to our cousin Dave Mentzel’s memory of Mark playing with all the younger kids at my dad’s funeral as he would have played with me, then I know for sure that I’m remembering him right.

I have another memory from around 1961, when I was in junior high and the extended family was gathered, possibly at Bobby and Joan’s. I hadn’t seen Mark for a while, maybe because he’d been in the seminary. As the adults droned on, the kids got restless, and a pack of us went wandering around the neighborhood. Mark suddenly launched into the Sharks and the Jets dance from West Side Story, leaping and twirling down the street like he was George Chakiris. As I was beginning to realize that I had a quirky creative mind, I immediately ID-ed Mark as a kindred spirit.

But again, we lived in different places, and life was taking us in different directions. He came to Grandma Beste’s funeral in May 1967. But all the Beste clan came with their accompanying clamor, and my memory of that event is a blob. During the three-day wake, my brother Bob, cousin Glenn, and I hid out periodically in the casket display room for R&R. At the burial, my dad said, “Go tell Grandma good-bye, Barbara Ann,” and I’m sure that’s a direct quote. But otherwise, too much was going on with too many people. I have the sense that Mark was quieter and more reserved, but after all, it was a funeral. On the other hand, we now know it was the year after Mark had met and fallen in love with Cecil, and so I’m guessing issues over that were already roiling his immediate family.

After that, other family members agree, it was as if he didn’t exist. We must’ve gotten minimal news at first, since I knew he was gay and Cecil was black and they were in Chicago. But the extended family’s take was that Mark was being boxed out and questions about him were sharply unwelcome. We were unsettled over this radio silence, anxious over his disappearance and unsure for years whether he was still alive.

For me, his absence was a sorrow, more so now that I know how terrible and unnecessary it was. I’m angry that we missed time with him and knowing his life as it was happening. Like the Maya Angelou quote about how we forget what people said or did but remember how they made us feel, I remember time with Mark as playful and affectionate and always special. When I was naming my kids, I often rejected names I liked because they reminded me of people I didn’t. But I chose the name Mark for my son because it came with the remembered love of a special cousin.

Thank you so much for reclaiming him.

Much love,

Barbara Beste Esstman